Written by Aidan Dunne for Taffina Flood’s solo exhibition Work + Turn, 2021.

Early on in Michelangelo Antonioni’s film Blow-Up, the main protagonist, Thomas, an ultra fashionable photographer, wanders into the studio of his neighbour, Bill, an abstract painter, and finds him staring at a work he made five or six years previously. Bill explains that his paintings, which are pointillist abstracts (and very good ones; they are actually works by Ian Stephenson, rather than purpose-made props), have no paraphrasable meaning for him until he finds something to hang onto in them. Thomas turns his attention to a new work lying on the floor. “Don’t ask me about this one,” the artist says. “I don’t know yet.”

Thomas asks if he can buy it; Bill declines. Nor will he give it to him. It is as if what Thomas really values is the mystery of the painting. The encounter anticipates and, more, encapsulates the core of the film, later prompting Thomas to examine in detail one of his own photographs, unearthing information in the image that he had not noticed when he took it.

The film’s script was very loosely based on a short story by Julio Cortázar. While working on the script, Antonioni visited Stephenson’s studio, and it seems fair to say that the visit was central to the development of the film: Stephenson’s paintings, and the questions about interpretation and perception they invite, are absolutely key in Blow-Up. In fact, they occupy a position that is exceptional in cinematic fiction.

At the time, asked about his approach to writing a scenario in an interview with Pierre Billard, Antonioni commented that: “I look at everything, avidly … an idea almost always comes to me through images.” Rather than devising or inventing images that clarify a dramatic line or illuminate the characters, the creative effort for him “has to do with restricting the accumulation of these images, with digging into them, with recognising the ones that coincide with what interests me at the time. It’s work done instinctively, almost automatically, but it involves a great deal of tension. One’s whole being is at stake….”

Much of the approach described by Antonioni, and much of the rationale applying to images and perception in Blow-Up, holds true for Taffina Flood’s paintings and print works. She is an avid collector of images, whether in her mind or as photographs: tens of thousands of photographs. But, by her own account, the photographs are not amenable to categorisation in terms of conventional genres. While they are certainly drawn from her environment, and one could say they touch on aspects of landscape, they are not really landscapes per se. Nor do they fit obviously into any other pictorial mould. While her photographs feature myriad ordinary things, they do so in a fragmented, even disjointed way, avoiding the standard motifs and compositional formulae that dominate the vast bulk of the staggering amount of photographic images in circulation, whether in material or virtual form. As one member of her family observed, with a level of puzzlement:

“Your photographs have no people in them.”

There is clearly something about each image that compels Flood’s attention but, as with the painter in Blow-Up, she is not consciously aware of what it is. The photographs certainly inform the paintings. It seems accurate enough to say that there is an ongoing dialogue between photographs and paintings. Painting, for her, is surely a way of interrogating the limitless body of potential images, of zeroing in on the heart of the mystery. And it is a process charged with tension. It involves, as she puts it, “a constant battle to get away from your conscious mind.”

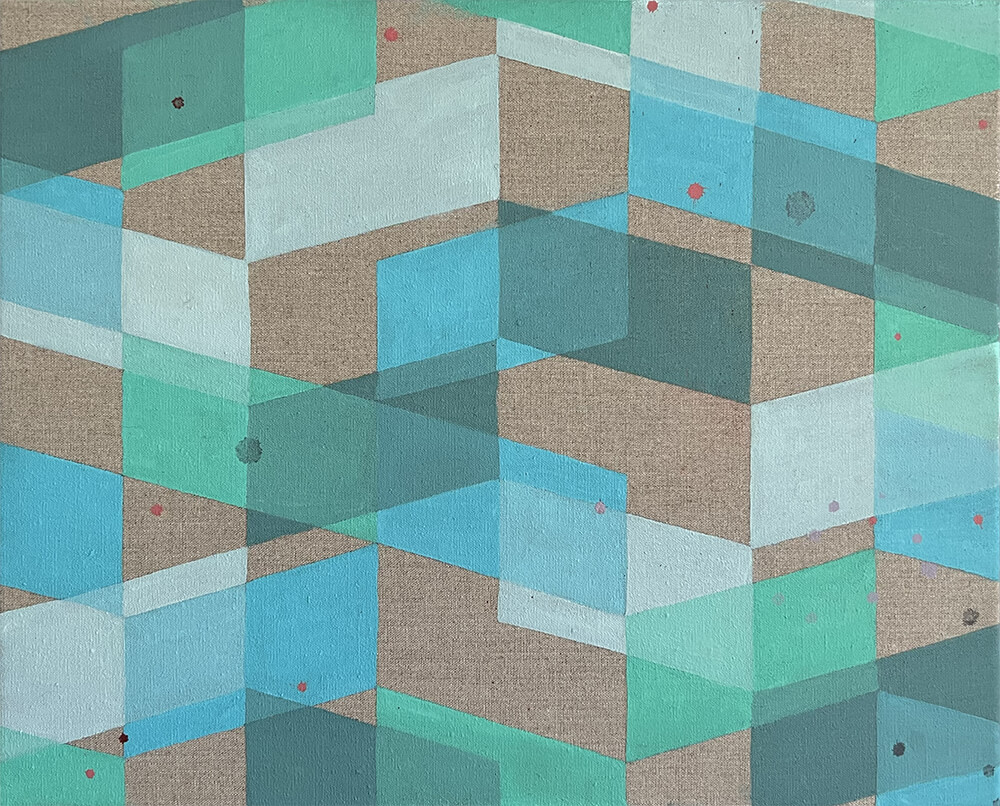

The process can be prolonged, involving over-painting and rediscovery, finding and losing and finding again, the search for half-remembered colours of uncertain origin, a dance of folds and twists of forms that are both geometric and organic. The format is always a square, a symmetrical framework which ensures she can work and rotate the composition as she goes along — hence the overall title, Work-and-Turn.

A history of its making is implicit in each painting, but the object is not to provide a visual record of a prolonged struggle with materials

(a viable, alternative strategy employed by some artists). In fact, if she feels she has gone too far with a piece, that it has become too clogged, she will simply abandon it. In the end, what remains, what we see, has to be in its own moment, instantaneous, everything or nothing.

In arriving at that point, she steers clear of the predictability of description. Description is something to be avoided. Representational images offer a form of reassurance. Once a scene knits itself together before our eyes, we know where we are, so to speak. Flood aims to disorientate us, to dislodge us from a position of habitual control and leave us in a different kind of space, one that requires renegotiation on our part, and a certain openness.

She alludes to walking as being important to the process. What she likes is the chance, unfiltered nature of “thinking walks”, when the raft of one’s own concerns and preoccupations meet the physical environment in unpredictable ways. Walking, as Rebecca Solnit put it in her book Wanderlust, provides an opportunity to “find what you don’t know you are looking for.” She elaborated on this idea in A Field Guide to Getting Lost, prompted she has said by a quote from Plato’s Meno that one of her students had jotted down: “How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is unknown to you?” Flood’s most concise answer to that question could be, simply: Painting.

Aidan Dunne